RiskVA

Nature’s Most Dangerous Animal – Us 16 Oct 2001

This column was originally intended to provide glimpses of the wild plants and animals found in the fields and forests of East Texas. For almost four years, it’s done that. At the same time, it is important to realize that humans are animals too, just more capable of abstract reasoning and communication than others. With that thought in mind, let’s take a look at ourselves - we, us, you and me, Homo sapiens, people - the most complex and confusing animals on earth.

All animals need food, water, shelter, light, and a suitable, if not always safe, environment. Competition among and between wild animals is ongoing in the outdoors. Territory is established, trespassers are confronted, often bluffed, and occasionally battled. Some come away winners and others losers. Defeat is often costly in terms of lost territory, restriction in social interaction, injury, and sometimes death. Nevertheless, wildlife combat is usually straightforward, waged with claw and fang. Humans, on the other hand, have contrived, often through technology, a far wider variety of diabolical means for hurting and killing each other.

Over the past two weeks, the people of this country have been confronted with the disease anthrax, caused by pathogens found in soil and naturally afflicting a wide variety of animals. Apparently, it has now been used as a biological weapon. One man died from inhaling disease spores and a woman is currently infected with cutaneous anthrax, a relatively easily treated form of the malady that causes ulcerated sores on the skin. Other exposures appear to have taken place as well. The future seems uncertain and many feel that a new, unheard of type of attack has taken place. Actually, what has happened is neither new nor unheard of. Biological warfare has been going on for hundreds of years.

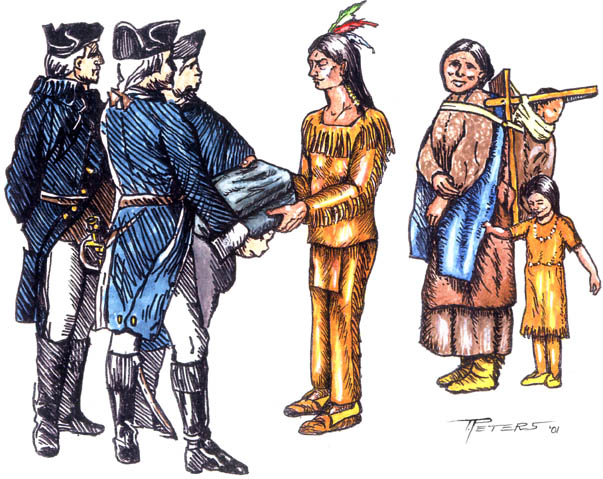

According to the Journal of Emedicine, July 2001, Scythian archers as long ago as 400 BC, dipped their arrows in excrement mixed with blood. Persians, Greeks, and Romans used dead animals in 300 BC to contaminate wells. In the 12th and 14th centuries AD, the bodies of dead soldiers were used for the same purpose and also to start plague epidemics. During the French and Indian War, British forces in North America created decimating smallpox epidemics by giving contaminated blankets to Native Americans. Germans, in World War I, allegedly spread plague in St. Petersburg, and infected mules with glanders in Mesopotamia. The Japanese, during the Second World War, performed ghastly experiments on Chinese prisoners involving plague, anthrax, and syphilis. In Vietnam, Vietcong guerrillas coated concealed, sharpened bamboo stakes with human feces to impale and infect opposing troops. The Soviet Union and their allies were suspected of using mold toxins called “yellow rain” in Laos, Cambodia, and Afghanistan. In 1984, 750 people became ill when Salmonella organisms were deliberately put into food by a radical group in Oregon. In 1994 a Japanese cult tried unsuccessfully to spread anthrax in Tokyo.

So here we are, at the beginning of the 21st Century, involved in territorial disputes, raging over religious differences, competing for food, power, and prestige, and behaving a little like high-tech wolves snarling at each other. Some of our species are toying with biological weapons that have devastating potential. Nevertheless, the tasks before us are not insurmountable unless we let fear conquer reason. Biological warfare has not destroyed humanity in the past and is unlikely to do so in the future. Granted, casualties could be very high, but nature teaches the important lesson that life is resilient and innovative.

I personally believe we are capable of virtually anything to which we set our minds. Moreover, while we may be similar in many respects to wild animals, we are also markedly different. Wildlife exists under constant stress, uncertain of survival from one moment to the next. Yet, they go on with life and even find the time and inclination for recreation. Can we do less? I think not. This is a time to display our finest attributes as we turn to inner, intangible support systems of spiritual faith and increased awareness of the brotherhood and sisterhood of humanity. We must reaffirm our need for each other and find the mutual strength that awareness brings. We can improve our circumstances, learn tolerance, and cope. While we must demonstrate increased vigilance, this is not a time for despair. We are, and always have been “one nation under God” and that, coupled with our intellectual powers, courage, and an unfailing belief in ourselves will carry us successfully through this crisis.

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.