RiskVA

Lightning – High-Voltage Nature 26 Jun 2013

Lightning season is upon us and we’ve seen numerous displays over the past several weeks. Exciting and fun to watch, lightning is one of nature’s most powerful, uncontrollable, and dangerous phenomena. We rightfully regard lightning with awe and fear. According to data published by the British Royal Aeronautical Society, there are 24,000 lightning deaths and 240,000 injuries worldwide each year.

Lightning is a huge spark of electricity that can leap as far as five miles from a cloud to the ground, from cloud to cloud, or within a single cloud. Even if there are no clouds nearby, if you can hear thunder, lightning may reach you. A lightning bolt’s tremendous surge travels at 60,000 to 90,000 miles per second, instantly heating the air to as much as 50,000 degrees Fahrenheit – three times hotter than the sun’s surface – and compressing it into a shock wave that races outward at 1100 feet per second. The arrival of the shock wave is what we hear as thunder. Count the seconds between the flash and the boom to determine how far you are from the strike. For example, 5 seconds equals 5500 feet, or just over a mile.

The average lightning bolt lasts only 1/10,000 of a second but it packs energy as high as 150 million volts at 125,000 amps. That’s enough electricity to run a 100-watt light bulb for three months!

A lightning bolt is produced when negative electrical charges form in clouds and positive charges develop on the ground or in other clouds. When the charge differences become great enough, a “stepped leader” forms an ionized path between them. Then in the tiniest fraction of a second the main charge that we see as the lightning flash blasts through the air. Sometimes ten or twelve discharges flicker rapidly along the initial strike path.

Lightning Safety

Weather experts recommend that at the first sign of a thunderstorm you should:

- Leave exposed places like baseball diamonds, soccer fields, golf courses, and lakes.

- Come down from high ground. Don’t be the tallest thing in the area.

- Don’t get under or remain near isolated trees or in small metal picnic shelters.

- Never use phones during a thunderstorm unless they’re wireless. Lightning sometimes travels down phone lines and kills people.

- Don’t use appliances and power tools connected to power outlets.

- Avoid metal or wire fences. Lightning can travel for miles along them.

- Stay away from open windows.

- Get into a car or truck. Even if lightning strikes it, the current will pass through the vehicle body, leap around the tires and pass harmlessly into the ground. (The insulation of the tires has nothing to do with your safety.)

- If you cannot get to a safe area, crouch down on the balls of your feet and cover your ears to protect them from sound damage. Do NOT lie down flat on the ground.

Atmospheric electricity comes in various forms. Two unusual types are ball lightning and St. Elmo’s Fire.

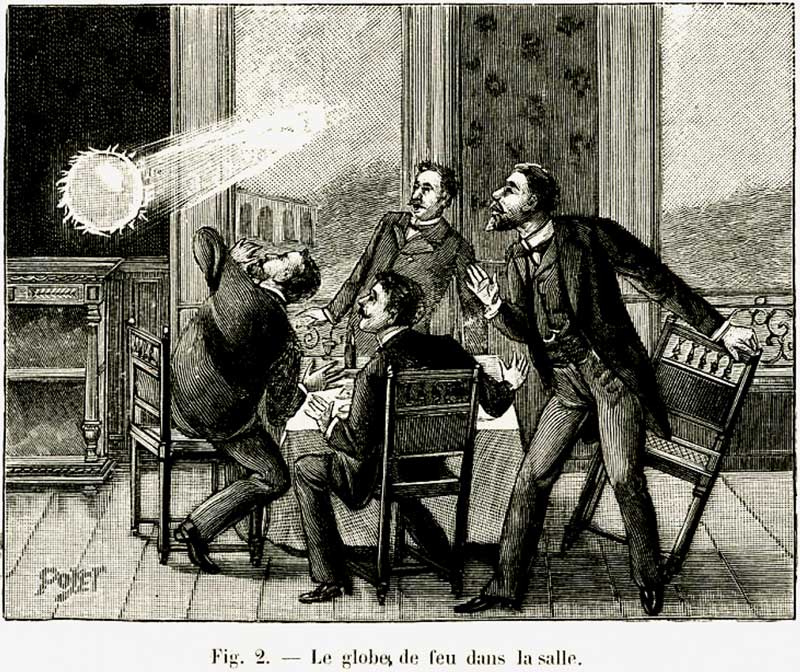

Ball lightning is very rare and poorly understood. Varying from the size of an orange to larger than a basketball, it may drift slowly down from a cloud, tree, or pole after a lightning strike, roll along the ground, or as in one reported case, roll through an open door. Some have come down chimneys and through window screens. Lasting only three to five seconds, these balls emit a sizzling sound and the smell of hot metal or ozone, then either silently disappear or collapse with a loud bang.

St. Elmo’s Fire sometimes appears on pointed objects such as antennas, aircraft wing tips, cattle horns, treetops, and even people’s heads as a humming, flickering, bluish corona. See this link for an interesting description of the accompanying photograph in this article. Mountaineers have mentioned hearing the “humming of bees” and seeing St. Elmo’s Fire on trees and pointed rocks just before a lightning strike. This strange phenomenon means that high energy electricity is present and lightning may follow without warning. Whether it’s humming, static in your hair, St. Elmo’s Fire, or simply thunder, take appropriate shelter. Don’t become a lightning season fatality.

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.