RiskVA

Prehistoric Bloodsuckers 30 Mar 2016

The world has been plagued by bloodsucking mosquitoes for about 100 million years. There are 3000 species of them worldwide; 200 species in North America. A significant number are naturalized Texans, and they’re on the prowl again.

It’s spring, and balmy temperatures lure us into gardens and parks. Nice time of the year. But what’s that whining sound approaching my ear? Rats! Tiny prehistoric, vampire-like mosquitoes are after me! But they haven’t arisen from moldy catacombs and caskets in Transylvania. They’re local citizens. (Actually, the vampire legends originated in Serbia, not Transylvania. Sorry to let you down.)

Similar in some respects to military drone aircraft, mosquitoes are outfitted with multiple sensors to help them find their meal. Their targeting arrays are sensitive to warmth, carbon dioxide, potassium, salt, and lactic acid so it helps to avoid salty and potassium-rich foods like bananas, avocados, and dried fruit.

Lactic acid is produced by sweaty exercise. Walkers, joggers, and other masochists emit a wave of both carbon dioxide and lactic acid that mosquitoes can detect over 100 feet away.

Do you smell nice? Maybe, but perfumes and scented lotions attract mosquitoes. It’s best to omit applying the sweet smells until after you exercise.

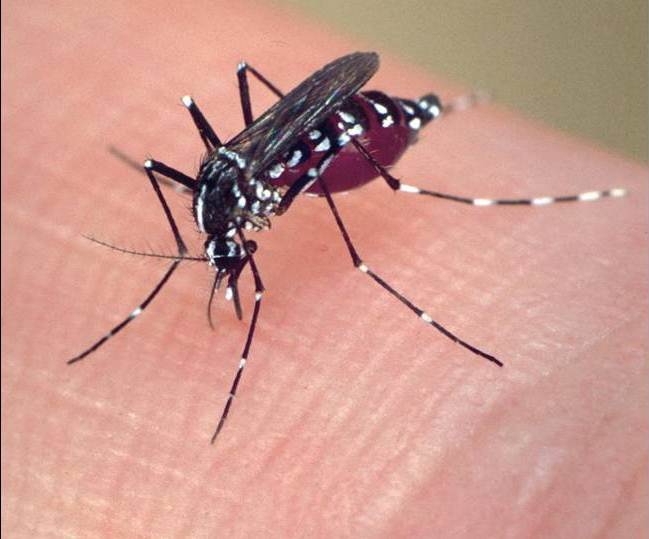

A mosquito’s head is mostly eyes. Two large, multifaceted, compound eyes bulge from the sides of their head. Hundreds of tiny “lenses” give each of them a wide area of vision and are particularly sensitive to even the slightest motion.

Mosquitoes feed not just on people but also on dogs, frogs, deer, squirrels, horses, and other animals. So don’t feel like you’re alone.

In the mosquito world, blood drinking isn’t a masculine thing. Only female mosquitoes bite and drink blood. Males feed genteelly and delicately on nectar, plant sap, or honeydew, as do females, but males don’t partake of blood. The guy’s main job is reproduction.

Mosquitoes begin their lives as eggs that develop into larvae, pupae, and adults in standing water. Rainwater trapped in discarded cans and other containers, or old tires are good breeding places. But almost any puddle or pond will do. They become adults in 4-7 days and begin their search for food and mates. Some adults even overwinter in freezing temperatures, their bodies bolstered with glycerol – antifreeze – awaiting warming temperatures to become active. Mosquito eggs can be dormant throughout the winter, awaiting spring weather to hatch.

A wide variety of diseases are carried by mosquitoes, including several kinds of encephalitis, malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, and more recently, chikungunya and Zika. The list is growing. They also carry West Nile virus, which is a serious, sometimes fatal disease. Domestic cats and dogs can become infected with heartworms transmitted by mosquito bites.

When a mosquito bites, it carefully inserts razor-sharp stylets into the victim and then probes with its proboscis for a blood vessel. The blood collection begins when they enter a tiny vessel, a process that they are not very good at. Scientists say that mosquitoes are only about 50% effective in finding a vessel. It then injects saliva containing an anticoagulant to keep the blood flowing, and an anti-inflammatory chemical to make the process as painless as possible so you won’t swat them. Disease organisms are also carried into the victim in the saliva.

Discouraging mosquitoes is hard. Bug zappers – those electrical cages with UV lights – don’t attract mosquitoes very well, but they do kill hundreds of beneficial insects every night. The best repellents are those containing a high percentage of DEET (diethyl-meta-toluamide). DEET also dissolves plastics, so be very careful about getting it on sunglasses or prescription lenses, and other plastic items.

So, we’ll just have to put up with them and take precautions, particularly from dawn to dusk, with repellents and by wearing long sleeves and long pants as we wander in the fields and forests. At least these tiny vampires, unlike Count Dracula, won’t turn you into one of their own with a nip of your neck. Our fields and forests aren’t that scary – yet.

Dr. Risk is a professor emeritus in the College of Forestry and Agriculture at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Content © Paul H. Risk, Ph.D. All rights reserved, except where otherwise noted. Click paulrisk2@gmail.com to send questions, comments, or request permission for use.